France: The Struggle to Defend the French Pension System

Lisbeth Latham

Since December 5, France has been gripped by ongoing strikes and mobilisations by a coalition of trade unions, high school and university student unions, as well as the gilet jaunes (yellow vests) to defeat the attack by the Macron and the Philippe government on France’s pension system. Whilst the alliance has been able to sustain a period of heightened mobilisations that have put the government under pressure, it remains unclear that the movement is powerful to defeat the attack, and there are serious barriers if the movement is to expand and grow.

Pension Counter Reforms

During the 2017 election campaign, Macron promised that he would look to “reform” France’s pension system. The current attacks both build on the changes to the pension system pushed through by the Sarkozy and Fillon government in 2010, and the failed attacks on the Special Retirement Plans for workers in a number of public services and recently privatised companies, launched in 1995 and 2007. These attacks have been justified on the need to make the pension system sustainable in the face of France’s ageing population (France’s pension system relies on pensions being paid out on the payments of current workers, with excess payments going into an investment fund).

The changes affecting the majority of French workers would increase the age which workers could access their pensions to 64 (in 2027) up from 62 years of age currently (Pivot Age), increase the period of time that workers have to have been working in order to qualify for a full pension from 42 to 43 years, and increase the age at which workers can retire on a full-pension without which working the minimum qualifying years work (Equalising Age).

The Special Retirement Plans refer to 42 different pension schemes received by workers in 15 organisations including rail workers with SNCF (French National Railway Company) and RATP (Autonomous Operator of Parisian Transportation), members of the Paris Opera, lawyers, members of the army, sailors, and the National Police. Workers in these primarily public organisations had had pension schemes (some of them dating back to Louis XIV) that had been in place prior to the introduction of the national pension scheme in October 1945. The Special Retirement Plans, tend to allow earlier retirement – many of these jobs are extremely physically strenuous, provide for workers to receive a higher defined benefit than the standard pensions, and have better indexation (the standard pension is indexed at inflation, whilst the majority of the Special Retirement Plan pensions provide for workers to have their pensions to be indexed with wage increases in their former industry). This attack on these has been justified on the basis of providing transparency and equality to the French pension system and would also secure the financial basis of the pensions in these plans (all of which are in sectors in which there have had significant contraction in employment and so there are substantial more retirees dependent on the pensions than workers contributing to the schemes), with the aim of splitting opposition to the pension reform.

Union Responses

Opposition to the proposed changes have been premised on four major arguments:

First that the changes will disproportionately affect women, who due to the socialised norms around responsibility for child-rearing means that women are more likely to have substantial career breaks and already many French women are unable to qualify for a full-pension prior to reaching pivot age, unions argue that increasing both the qualifying period and the full-pension age will cast greater numbers of women poverty in retirement - currently, women who have children are given credit towards their pension qualification, 1 year per child in the public sector, two-years per child in the private section, the proposed changes would remove this. Women currently receive 29% of the pensions of men, however, the CGT (Confédération générale du travail - General Confederation of Labour) expects this gap to rise to 42% if the current protections for women are removed as proposed.

Secondly, that increases in the pension ages mean that workers will increasingly be unable to retire prior to the onset of the illnesses of old age, and so fewer and fewer workers will be able to have a healthy period of retirement prior to the onset of these illnesses.

|

| Your pharmacist recommends retirement before arthritis |

industries. These workers currently are able to retire earlier, the extension of the pension age will put heavy pressure on the bodies of these workers to be able to work to the new pension age. Whilst the government has pulled back on the removal for some categories of workers, notably police and firefighters, sewage workers, who on average die seven years earlier than other workers and 17 years earlier than managers, will lose their current early retirement.

Finally, that workers who lose their jobs later in their working lives, who already find it difficult to obtain work, will have to face a longer period of either unemployment or underemployment prior to reaching the pension age.

Convergence of struggles

The present movement draws together separate struggles that have been occurring in France during the Macron presidency. The left has, and the more militant unions have sought to draw together and converge the existing struggles within French society into the pension struggle. This has included pre-existing workers' struggles but has also included movements of students that have campaigned against both fees and the introduction of increased university entrance requirements which has seen thousands of young people fail to gain entrance to university and the introduction of increased student fees for international students and the mobilisation of thousands of university and high school students which has seen schools and universities blockaded and the call for exams to be totally cancelled to allow the full involvement of students in the movement. This process of convergence is not new, and his been an objective of a range of militant organisations since prior to the Macron presidency, and particularly in relation to the emergence of the Front Social and the Nuit Debout during struggle against the El Khomri attacks on the Labour Law and the gilet jaunes as a new force mobilisation which, since November 2018, has drawn into motion sections of the French popular classes that unions and other progressive forces have not been able to mobilise for an extended period of time.

State and Government Responses

In response to the mass movement the state, just as it has to other mobilisation since the November 2015 introduction of the (withdrawn in November 2017) state of emergency following the terror attacks in Paris, has responded with escalating repressive violence. There has been widespread footage of CRS (Republican Security Companies) and Gendarme riot police beating protestors, as well the deployment of a range of “non-lethal” weapons, including explosive tear gas grenades (France is the only European country to deploy explosive canisters in law enforcement) and flash balls, that has seen a steady rise in the number of people who have been maimed at protests.

In addition, the government has sought to manoeuvre in the hope of dividing and blunting the movement. The tactic has been the announcement of the “temporary” withdrawal of the first phases of the increase in the Pivot Age, that had been scheduled to begin in 2022. A withdrawal that is based on finding an alternative way of saving €12 billion “in order to secure the system by 2027” - the government has proposed a conference on January 30 to identify alternative mechanisms to make savings in the pension system. The “concessions” have primarily been aimed at the conservative unions, particularly the CFDT (Confédération française démocratique du travail - French Democratic Confederation of Labour - the largest French confederation when measured by the number of members and second-largest in employee representative bodies) and UNSA (L'Union nationale des syndicats autonomes - National Union of Autonomous Trade Unions, which is the second most popular union within both the SNSF and RAPT), who have responded positively to the concessions, with CFDT general secretary Berger calling the withdrawal of the 2022 Pivot Age phase-in date a victory for the CFDT and called on CFDT members to desist from participating in strikes and mobilisations against the pension reform. However, the more militant unions have rejected the overtures of the government, arguing that legislation is not amendable and that it should be withdrawn. The CGT, in a January 11 statement said, “that debate on the Pivot Age is simply aimed at winning the support of certain unions”. Léon Crémieux, a militant in SUD Rail, the trade union Solidaires union within the SNSF and RAPT, and leader of the NPA (Nouveau parti anticapitaliste - New Anticapitalist Party), argues that the conference is a trap which “ is going to close quickly since this conference will only be able to put the “pivotal age at 64” back in the frame, forcing retirement two years later, or lengthening the number of years worked necessary to retire (43 years today)”. SUD Rail, in a statement on January 24, said it would refuse to meet with the government and would continue to mobilise its members until the withdrawal of the bill.

The current movement has significant weaknesses

Despite significant public support, opinion polls suggest that support for the movement has reached peaks of 65%, however, the movement has failed to not only meet that level of support but the size and breadth of the major working-class mobilisations of the past three decades.

This has meant that the current movement is substantially bigger and longer-lasting than the peak of the counter government movements of the last decade, but the movement is substantially smaller than the big movements against government attacks against the working class of the last three decades, particularly the movements of 1995, 2003, and 2010. In 1995, the movement was primarily within the public sector, and was not directly supported by the more conservative unions particularly the CFDT, but were driven by the CGT and FO (Force ouvriere - Workers Force) - however, the more militant unions were able to draw much broader layers of the working class, including significant sections of the CFDT’s membership and support base, into motion. 2003 the movement against the first employment contract, which focused on the employment rights of young workers,, was primarily driven by mobilisations by students and education workers. The 2010 movement to defend the pension system, peaked at mobilisations of 3.5 million, and seven mobilisations of more than 2 million across eight weeks, in addition there indefinite strikes in a number of industries particularly oil refining which resulted in widespread fuel shortages. However despite the larger size of these earlier movements, they at best achieved partial victories, and in the case of 2010 movement, it failed totally and demobilised on the promise that a future Parti Socialiste (PS) government would repeal the changes - which the PS government never attempted to do, instead it introduced new attacks on the unions and France’s working class. Defeats which have contributed to the current inability of the movement to spread.

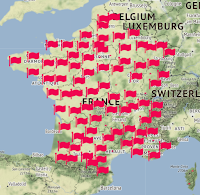

At the same time the ability of the movement to sustain itself and force the government to offer “concessions” has given hope that perhaps the movement can outlast the resilience of the government or potentially capital. Importantly, the movement has been expanding, the more than 200 mobilisations across France on January 24, drew an estimated 1.3 million people onto the street up from 800, 000 on January 16. At the centre of the struggle has been the strikes within the SNCF and RATP with 45 days of strike action which ended January 24. This strike was initiated by the militant union federation within both SNCF and RATP, and was primarily built on the back of the September strike within RATP against pension reform. Other key areas have been the depth of the struggle within France’s cultural institutions particularly the Paris Opera, which has been on strike and performing at the mass demonstrations in Paris, the Louvre, and the French National Library, the blockading of oil refineries which occurred between January 8 to 11. On January 24, the CGT stated it was seeking to initiate discussions with workers in those workplaces not yet on strike, to draw them into action. This is occurring through the holding of general assemblies of workers and at the workplace and municipal level. Whilst the inability to draw the more conservative unions, particularly the CFDT consistently into the movement is a real weakness and break on the movement’s potential to mobilise, it potentially could be a strength, as it reduces the influence of the CFDT on the movement and government cannot rely on the CFDT’s sudden withdrawal from the movement, which happened in 2010 after the pension changes were passed, to undermine and demobilise the movement. This has the potential to place considerable additional pressure on the government, as it is less likely, compared to 2010, that the movement will simply evaporate following the passing of any legislation. Added to this, with the splintering of the PS in the wake of the 2017 presidential elections, it is hard for more conservative forces to advocate an electoral solution to addressing the assault on pensions.

The current national intersyndicale which brings together the CGT, FO, CGC-CFE (Confédération française de l'encadrement - Confédération générale des cadres - CFE-CGC), the trade union Solidaires, FSU (Fédération syndicale unitaire - Unitary Union Federation), FIDL ( Fédération indépendante et démocratique lycéenne - Independent and Democratic High School Federation), MNL (Mouvement national lycéen - National High School Student Movement), UNL (L’Union nationale lycéenne - The National High School Union), and UNEF (Union Nationale des Étudiants de France - National Union of Students of France) has called for three further days of mobilisation on January 29, 30, and 31. These days of mobilisation will be an important test as to the direction of the movement’s inertia.

This article is posted under copyleft, verbatim copying and distribution of the entire article are permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved. If you reprint this article please email me at revitalisinglabour@gmail.com to let me know. Read more...